The Objective Facts Behind Elorza’s Plan to Sell Providence Water

Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza’s plan to monetize the city’s water supply is ideal material for a four-part mystery series with a twist ending.

In part one, entitled Status Quo, the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission keeps the lid on the rates charged by Providence Water, constraining the utility to earn a zero rate of return. (Yes, zero.) So it’s a mystery why any potential buyer of the city’s water supply would have the remotest incentive to do so.

In part two, entitled Political Persuasion, we find out whether the city’s lobbyists can convince our state legislators to strip away the Public Utility Commission’s regulatory jurisdiction over Providence Water. In part three, The Negotiations, we learn whether the recently reported “serious discussions” with the Narragansett Bay Commission about acquiring Providence Water are really serious.

Part four is, of course, The Denouement. Once the General Assembly gives the Narragansett Bay Commission the green light to acquire Providence Water, we find out how much our the newly deregulated public water utility hikes its rates to finance the acquisition, after having denied all along that it would do anything of the sort. If rates rise to anywhere near what customers currently pay for their water in Newport, the extra money forked over by Providence consumers may cover the entire acquisition cost in a little over a decade. So, we end up financing a significant chunk of our pension legacy through our clean, clear water bills.

What a splash.

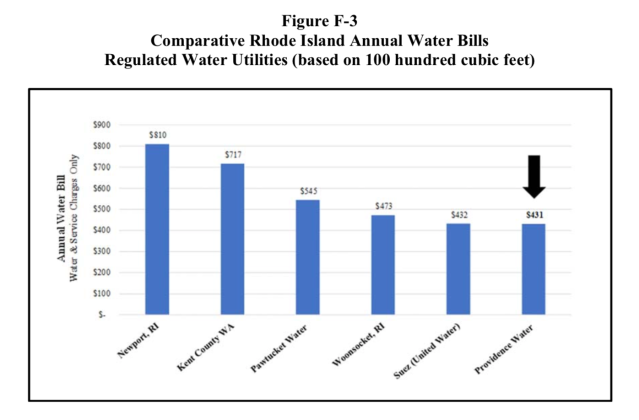

Source: MRV Valuation Consulting LLC, Valuation of Providence Water Supply Board Water Assets, August 8, 2017, Figure F-3.

Why would anyone want to acquire Providence Water’s assets?

In its October 2017 report to the city, MRV Valuation Consulting made it crystal clear that the group of potential buyers of our water resources is actually quite limited. Basically, it comes down to the Narragansett Bay Commission and three surrounding water districts — the Pawtucket Water Supply Board, the East Providence Water District, and Bristol County Water Authority. MRV also considered SUEZ Rhode Island, a private investor-owned utility serving Washington County, but Elorza appears to have firmly ruled out the option of privatizing our water supply. The consultants referred in passing to the possibility that the state itself could buy or lease Providence Water through some sort of quasi-governmental agency, but that option appears to be totally off the table.

Why would any one of these potential public or private buyers have any incentive to acquire Providence Water? Ordinarily, a buyer wants to acquire an asset because it can earn a return on its investment. But the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission, exercising its regulatory control over Providence Water, sets the utility’s rates to a zero rate of return. Here’s how MRV described the situation in its transmittal letter.

Due to Rhode Island regulation, the Providence Water Supply Board is subject to rate suppression and a “pay as you go” infrastructure program. They are not allowed to earn a rate of return on its rate base. Any monies approved by the Public Utilities Commission must be paid back with principal and interest and zero profit is allowed. [My emphasis.]

It’s basic economics that the market value of an asset is the present value of the stream of its current and future earnings. But in this case, the present value of Providence Water’s financial surplus is zero. State regulation has made Providence Water worth nothing.

How much is Providence Water really worth?

Our local press has repeatedly cited the MRV’s estimate that the city’s water resources are worth $404 million. Yet MRV itself made it abundantly clear that this figure is not necessarily an accurate indicator of market value, but only an estimate the reproduction cost of the assets, less depreciation and obsolescence. “The basic concern surrounding the cost approach,” the consultants acknowledged on page 30 of their report, “is that cost may not equal value.” They further acknowledged, in fact, that the estimate was a “hypothetical valuation” made under conditions “contrary to what is known by the appraiser.” Here’s how MRV made the point in its transmittal letter.

The purpose of this analysis is to provide the City of Providence (the “City”) with a hypothetical valuation of the water assets owned and operated by the Providence Water Supply Board, as of March 31, 2017. The hypothetical condition is that the Providence Water Supply Board is to be considered a “special purpose” property and the analysis should only consider the cost approach to value, specifically “reproduction cost new, less physical depreciation, less functional obsolescence.” According to the Uniform Standards of Appraisal Practice (“USPAP”), a hypothetical condition is defined as “a condition, directly related to a specific assignment, which is contrary to what is known by the appraiser to exist on the effective date of the assignment results, but is used for the purpose of analysis.” [My emphases.]

MRV’s estimate of the reproduction cost of Providence Water’s assets was not without its limitations. When it came to explaining its calculations, the consultants’ report was notably short on key details. Without substantial additional inquiry, there is simply no way one can replicate their calculations or verify their accuracy.

For some of the utility’s assets, the consultants started with the historical acquisition cost, then inflated the original cost to an estimate of current construction cost, and then subtracted an estimate of physical depreciation. For example, the Gainer Dam, situated at the southeast end of the main Scituate Reservoir, was constructed in 1927 at an original cost of $3,430,846. Using the Handy-Whitman Index of public utility construction costs — which appears to be proprietary and was not disclosed — the consultants inflated this original cost figure to a current reproduction cost of $108,374,370 in 2017. (See their Appendix 3.) That comes to a multiplier of about 31.6 over 90 years. No plus-or-minus range is attached to this cost-inflation calculation. Then the consultants took $70,983,340 in accrued depreciation, which amounts to about 65.6 percent of the current reproduction cost, to arrive at an estimate of reproduction cost less depreciation of $37,931,030. The consultants explained in general terms that they employed a modified straight-line depreciation method. (See page 39 of their report.) But it remains unclear how they arrived at an accrued depreciation of only 65.5 percent for an asset in service for 90 years of its estimated 100-year life expectancy.

For the dam that forms the Moswansicut Reservoir, which was constructed in 1919, the consultants used an alternative approach based upon another proprietary source on construction costs, the RSMeans data. The details of the calculation were likewise not disclosed. For the remaining dams, including the Regulating, Barden, Ponaganset, and Westconnaug Dams, the consultants extrapolated the reproduction costs based on their storage capacity relative to the Moswansicut dam. They did not disclose whether their calculations were based on the Moswansicut dam’s total volume capacity of 1.8 billion gallons or its net storage capacity, excluding dead storage, of 0.9 billion gallons.

The consultants’ reproduction cost estimate was supposed to include a deduction for obsolescence. After all, if you start with an estimate of the cost of reproducing an asset, and you then take account of its physical deterioration, you still have to consider whether the asset uses the state-of-the-art technology. Here, the consultants made a combined $14.7 million deduction for “functional obsolescence” for just 2 of the 143 individual assets that they valued. The deduction was based solely on an estimate of the extent of water leakage from old or poorly constructed pipelines, inadequate corrosion protection, and leaky joints, valves and fire hydrants. The report contains no survey concerning the state of the art of any other Providence Water facilities.

As an alternative method of valuing Providence Water’s assets, MRV did look at comparable sales of other water utilities. The closest comparable sale of a water utility with approximately the same number of retail customers was the $327 million purchase in January 2016 of Park Water Company, which owned Mountain Water Company in Missoula, Montana and two other utilities in Southern California. But the purchase was made by Liberty Utilities, a private investor-owned company and the target of the acquisition was not subject to the zero-rate-of-return regulation currently imposed on Providence Water by the R.I. Public Utilities Commission. Mountain Water was ultimately taken over by the city of Missoula at an estimated cost of $114 million, to be financed in part through customer rate increases.

In short, Elorza’s assertion that the sale or lease of Providence Water could bring in between $300 million and $700 million lacks a reliable factual basis.

The Lead Problem

In a series of articles starting with Lead in Our Tap Water: Providence RI versus Flint MI, and continuing with Lead in Our Tap Water: Response to Providence Water and Lead in Our Tap Water: It’s Coming From the Public Side, I detailed the serious public health problem of lead in the tap water of Providence homes, particularly those on the city’s East Side. A major source of the lead contamination was the water mains running throughout the city. In the repeated rounds of legislative testimony, recriminations and editorials, nobody seems to have considered Providence Water’s ongoing liability to rid its water of lead contamination.

Back in 2012, the R.I. Department of Health and the U.S. Environmental Agency entered into a consent agreement with the Providence Water Supply Board that gave the Board extra time to clean up its lead problem. According to the Board’s most recent audited financial statement for fiscal 2016, further extensions were granted in succeeding years. A page on its website entitled “Where Does Providence Stand?” states, “Providence Water is currently negotiating a Consent Agreement with the RI Department of Health.” In a separate web page entitled “What is Providence Water Doing?,” the utility notes, “Over the last 10 years, we have spent over $45M replacing lead services.” How much more the utility needs to spend is not disclosed.

How much could water rates go up?

Narragansett Bay Commission chairman Vincent J. Mesolella Jr. told the local press that the Commission could come up with $300 million to acquire Providence Water “without causing a rate increase.” But Cynthia Wilson-Frias, deputy chief of legal services for the Public Utilities Commission, countered that it wasn’t clear how the Commission “could reasonably expect to purchase a $300 million asset absent a rate increase of some kind.”

(In 1993, North Providence Rep. Mesolella became both Deputy House Majority Whip and Chairman of the Narragansett Bay Commission. According to Phil West’s enlightening history, “During the two years after officers of New England Treatment Co. (NETCO) donated $2,125 to Mesolella, the commission paid their company $417,995.”)

Let’s calculate how much more Providence Water customers would have to pay to finance a $300 million acquisition. That would at least cover a chunk of Providence’s billion-dollar pension fund shortfall. Let’s spread the payment over 10 years, at $30 million per year. To keep the math simple and get an idea of the order of magnitude involved, we’ll ignore interest payments. Since Providence Water has approximately 75 thousand customers, the additional cost would be: $30 million ÷ 75 thousand customers = $400 per customer per year, which comes to about $33 per month. According to the MRV report (p. 14), a family in Providence currently pays an average of $36 per month. Thus, the financing of a $300 million acquisition through rate increases would require about a 92-percent increase in water bills. That would bring Providence Water’s rates in line with those paid by customers in Newport. (See graphic at the head of this article.)

Moving Money Around

So, here we have a mayor who claims that the city could raise between $300 million and $700 million from the sale or lease of Providence Water, based upon a replacement cost estimate of $404 million that the city’s consultants themselves have characterized as a “hypothetical valuation” made under conditions “contrary to what is known by the appraiser.” No potential buyer would even consider acquiring the city’s water assets unless the state Public Utilities Commission lifted the lid on its current zero-rate-of-return regulation of water rates. A bill introduced in the state House of Representatives would strip the Public Utilities Commission of its authority to regulate Providence Water’s rates for five years. While it would supposedly hold future rate increases to historical levels, the legislation explicitly requires that water rates should be sufficient to cover “the principal and interest on any bonds and notes.”

There is no evidence that the proposed transactions will achieve any improvements in quality or any economic efficiencies in the delivery of water to Providence Water’s customers. The proposals to date constitute no more than a scheme to move money around from one pocket to another. Despite various unenforceable promises about holding down water rates, the bottom line is that our future water bills will end up financing a big chunk of the pension liability of the City of Providence.

Or perhaps all the hubbub about selling our water assets is simply a sophisticated public relations scheme to create the false impression that the mayor has a workable idea how to eject the city from its massive, billion-dollar pension black hole.

![]()