The Beginning of Mexican-American History

The Mexican-American War

and the Beginning of

Mexica-American Hostory

CONTENS

* “Mexican-American history’s beginning” By Elaine Ayala, San Antonio Express-News (February 2, 2018)

* “America’s Forgotten War with Mexico” By Shane Quinn, Global Research (February 10, 2018)

Mexican-American history’s beginning

By Elaine Ayala

San Antonio Express-News (February 2, 2018)

Feb. 2 won’t ring a bell for anyone except perhaps historians and Chicano activists, who’ll know el segundo de Febrero commemorates the biggest boundary dispute in the nation’s history.

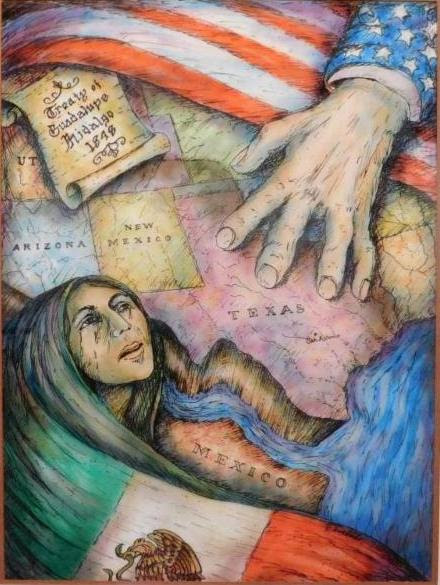

Feb. 2 won’t ring a bell for anyone except perhaps historians and Chicano activists, who’ll know el segundo de Febrero commemorates the biggest boundary dispute in the nation’s history.Better known as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it not only ended the Mexican American War but extended U.S. boundaries to Colorado and Utah and all the way west to the Pacific, setting the southern border at the Rio Grande.

In one fell swoop, a great, big chunk of land, 525,000 square miles, became the southwestern United States in 1848. It was a real-estate transaction forged by Santa Anna and Nicholas Trist, a U.S. diplomat.

Mexico lost the war and 55 percent of its territory. At the time of the treaty, American Indians were at war to protect it as their own, and not so surprisingly, were considered “hostile” by both Mexico and the United States.

Our southern neighbor got $15 million out of the deal, a sum some historians view as just. “That was a lot of money then,” said Trinity University scholar Aaron Navarro. “It’s a lot of money now.”

Others, such as economist Steve Niven of St. Mary’s University, scoffed a bit and called it a pretty good deal for the United States, given California gold, Texas oil and other subsequent riches.

For the largest Latino group in the United States, Feb. 2, commemorates the beginning of Mexican American history, the story of a people who are, at once, of one nation and another. That duality has defined and confused them and has confounded their fellow Americans.

It’s easy to feel angry about what happened to Mexican Americans in the years right after 1848, when the treaty was signed. In Texas, they became U.S. citizens automatically and were assured that their Mexican and Spanish land grants would be honored.

They weren’t. Many were cheated out of their lands by legal and illegal means, and some continue to fight to get them back. They’ve got colorful words for some of the state’s most hallowed ranchers. Thieves might be the mildest.

A generation or two after the treaty, there were more Mexican American laborers than landowners. Historian Patrick Kelly of the University of Texas at San Antonio calls the treaty one of the great unknown, understudied events in U.S. history, especially on the East Coast, where Southwestern borders may still be seen as Manifest Destiny.

Few groups mark el segundo de Febrero. More should, to better remind us of our past and how it has shaped our future. Since 1978, Centro Cultural Aztlán has led the way. Through the years, Centro Cultural Aztlán has chosen not to disparage the treaty as much as honor what it created.

“It gave birth to this dual identity,” says executive director Malena Gonzalez-Cid, “and a new political entity.”

For 165 years, in fits and starts, this new entity not only has been trying to grapple with its duality, but bridge it.

And it remains our inheritance.

This column by Elaine Ayala originally ran in the Express-News in 2013. She can be reached at eayala@express-news.net.

America’s Forgotten

War with Mexico

America’s war of expansion

over Mexico, backed by

newspapers and politicians,

has repercussions to the present day.

By Shane Quinn

Global Research (February 10, 2018)

Reflecting on his life while dying of throat cancer in 1885, the former US President Ulysses S. Grant said the Mexican-American War was, “the most wicked war in history. I thought so at the time, when I was a youngster, only I had not moral courage enough to resign”.

Reflecting on his life while dying of throat cancer in 1885, the former US President Ulysses S. Grant said the Mexican-American War was, “the most wicked war in history. I thought so at the time, when I was a youngster, only I had not moral courage enough to resign”.Grant had first-hand experience as he himself fought in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), then as a junior officer in his mid-20s. Less than two decades later, he rose to prominence as one of the most important figures during the American Civil War – as Commanding General his powerful Union Army finally crushed the under-resourced Confederates.

Grant would become a two-term American President (1869-1877), initially taking the job with reluctance. “I have been forced into it in spite of myself”, he wrote to William Sherman, a fellow Union Army general during the civil war.

Despite involvement in various conflicts, the Mexican-American War haunted Grant to the end.

“I had a horror of the Mexican War and I have always believed it was on our part most unjust. The wickedness was in the conduct of the war. We had no claim on Mexico. Texas had no claim beyond the Nueces River, and yet we pushed on to the Rio Grande and crossed it. I am always ashamed of my country when I think of that invasion”.

What is striking about Grant’s views today is how remarkably forthright they are. It would prove unthinkable for US presidents in later centuries to express ethical misgivings about the attacks on Korea or Vietnam, Afghanistan or Iraq – despite the much greater destruction and loss of life.

The defeat of Mexico consolidated US expansion of its territorial size by almost 25%. Texas had initially been annexed from Mexico in 1845, a state almost three times the size of Britain.

The Mexican government refused to recognize Texas’s illegal incorporation into American terrain. By May of the following year (1846), the US had declared war on its southern neighbor. US President James K. Polk utilized the pretext that attacking Mexican forces had “passed the boundary of the United States [in Texas], has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil”.

In truth, the “American soil” was Mexican soil annexed to become part of the US. The Americans were awaiting a ruse in which they could attack Mexico without causing unwanted popular uproar, allowing the US to make further gains into Mexican land.

In all the time since, there has been little demand from democratic leaders for the US to return Mexico’s stolen territories – or at least to recognize a gross injustice was inflicted upon her.

Instead, we hear hypocritical laments over Russia’s “annexation” of Crimea in 2014 – a region that was firstly part of Russia (from 1783-1917) and then later under the sphere of the USSR (1917-1991).

The principal purpose for America’s war of conquest over Mexico was gaining monopoly over cotton production. In the 19th century, cotton was as vital as oil is today, and also represented a key commodity of the slave industry. Control over cotton “would bring England to its feet”. President Polk openly recognized this, as did his immediate predecessor, former President John Tyler.

Indeed, Tyler said of Texas’s 1845 annexation,

“By securing the virtual monopoly of the cotton plant”, America had acquired “a greater influence over the affairs of the world than would be found in armies however strong, or navies however numerous”.

Tyler continued,

“That monopoly, now secured, places all other nations at our feet. An embargo of a single year would produce in Europe a greater amount of suffering than a fifty years war. I doubt whether Great Britain could avoid convulsions”.

The American victory over Mexico in February 1848, led to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. It saw the US take not only Texas from Mexico, but also California, half of New Mexico, most of Arizona, Nevada and Utah, along with parts of Wyoming and Colorado. Much of these areas were rich in cotton, with the conquests signifying an epic land-grab whose repercussions last to the current day.

In keeping with modern times, the Free Press championed America’s illegal interventions. James Gordon Bennett – editor and founder of the New York Herald – then the US’s biggest selling newspaper, wrote approvingly that Britain was “completely bound and manacled with the cotton cords. A lever with which we can successfully control” their main rival. Not a word of the unwarranted acts perpetrated against Mexico.

Indeed, Bennett was hopeful that the Mexicans’ fate would be

“similar to that of the Indians of this country – the race, before a century rolls over, will become extinct”. He wrote about the “imbecility and degradation of the Mexican people”.

Bennett was one of the major figures in the history of the American press, and felt that “the idea of amalgamation [of races] has been always abhorrent to the Anglo-Saxon race on this continent”.

The Cincinnati Herald editor described Mexicans as “degraded mongrel races”, along with Native Americans. The editor of the Augusta Daily Chronicle, in Georgia, offered prior warning in 1846 that attacking Mexico would likely reveal,

“a sickening mixture, consisting of such a conglomeration of Negroes and Rancheros, Mestizoes and Indians, with but a few Castilians [Spaniards]”.

In 1845 James Buchanan, future US President, insisted that

“our race of men can never be subjected to the imbecile and indolent Mexican race”.

Texas Senator Sam Houston went even further, saying in 1848 that

“the Mexicans are no better than Indians, and I see no reason why we should not go on in the same course now and take their land [all of Mexico].”

Walt Whitman, America’s famous journalist and poet, asked

“What has miserable, inefficient Mexico… to do with the great mission of peopling the New World with a noble race?”

With these prevailing attitudes, a quick, easy victory was expected over Mexico. However, it was anything but, as the Mexican Army fought valiantly, surprising its over-confident American foe. The conflict lasted almost two years, before the weight of superior US forces finally told.

Following Mexico’s defeat, a new artificial border was imposed which remained quite open. Those wishing to cross it to visit relatives or engage in commerce found it a straightforward affair. That is, until the 1990s, when the Clinton administration began fortifying and militarizing the Mexican border.

George W. Bush then aggressively expanded upon Clinton’s initiatives along the frontier – under the pretexts of shielding the US from illegal immigrants, terrorists or drug dealers.

The territorial gains over Mexico have largely been erased from memory, despite having occurred comfortably within the past 200 years. It seems plausible that many Americans living in Texas or California may be unaware they are sitting on occupied Mexican land.

The American writer and lecturer Ralph Waldo Emerson said,

“It really doesn’t matter by what means Mexico is taken, as it contributes to the mission of ‘civilizing the world’ and, in the long run, it will be forgotten”.

It has not been forgotten by Mexicans, however. In April last year Mexico’s former presidential candidate, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, urged his government to bring a lawsuit against America in the International court of Justice, for reparations and indemnification.

A lawyer working for Cardenas said,

“We are going to make a strong and tough case, because we are right. They were in Mexican territory in a military invasion”.

One suspects Ulysses S. Grant would be in their corner.

This article was originally published by The Duran. The original source of this article is Global Research

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky.